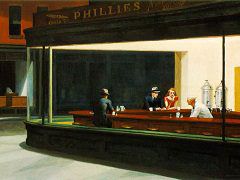

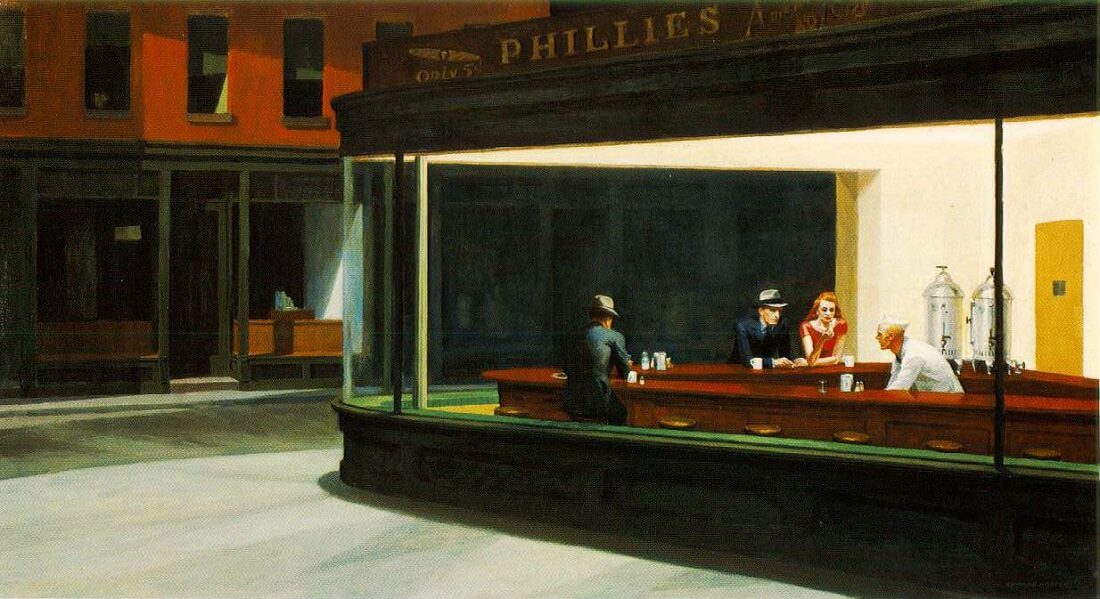

Nighthawks, 1942 by Edward Hopper

Nighthawks is a 1942 painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people sitting in a downtown diner late at night. It is Hopper's most famous work and is one of the most recognizable paintings in American art. Within months of its completion, it was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago for $3,000, and has remained there ever since.

Starting shortly after their marriage in 1924, Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine (Jo), kept a journal in which he would, using a pencil, make a sketch-drawing of each of his paintings, along with a precise description of certain

technical details. Jo Hopper would then add additional information in which the themes of the painting are, to some degree, illuminated.

A review of the page on which "Nighthawks" is entered shows (in Edward Hopper's handwriting) that the intended name of the work was actually "Night Hawks", and that the painting was completed on January 21, 1942.

Jo's handwritten notes about the painting give considerably more detail, including the interesting possibility that the painting's evocative title may have had its origins as a reference to the beak-shaped nose of the man at the bar:

Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Bright items: cherry wood counter + tops of surrounding stools; light on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 cross canvas at base of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, dull yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen right. Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back at left. Light side walk outside pale greenish. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant, dark Phillies 5c cigar. Picture of cigar. Outside of shop dark, green. Note: bit of bright ceiling inside shop against dark of outside street at edge of stretch of top of window.

The four anonymous and uncommunicative night owls seem as separate and remote from the viewer as they are from one another. (The red-haired woman was actually modeled by the artist's wife, Jo.) Hopper denied that he purposefully infused this or any other of his paintings with symbols of human isolation and urban emptiness, but he acknowledged that in Nighthawks "unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city."

Nighthawks was probably Hopper's most ambitious essay in capturing the night-time effects of manmade light. For one thing, the diner's plate-glass windows cause far more light to spill out onto the sidewalk and the brownstones

on the far side of the street than is true in any of his other paintings. As well, this interior light comes from more than a single lightbulb, with the result that multiple shadows are cast, and some spots are brighter than others as a

consequence of being lit from more than one angle. Across the street, the line of shadow caused by the upper edge of the diner window is clearly visible towards the top of the painting. These windows, and the ones below them as well,

are partly lit by an unseen streetlight, which projects its own mix of light and shadow. As a final note, the bright interior light causes some of the surfaces within the diner to be reflective. This is clearest in the case of the

right-hand edge of the rear window, which reflects a vertical yellow band of interior wall, but fainter reflections can also be made out, in the counter-top, of three of the diner's occupants. None of these reflections would be visible

in daylight.

Hopper's biographer, Gail Levin, speculates that Hopper may have been inspired by Café Terrace at Night by Vincent van Gogh, which was showing at a

gallery in New York in January 1942. The similarity in lighting and themes makes this possible; it is certainly very unlikely that Hopper would have failed to see the exhibition, and as Levin notes, the painting had twice been exhibited

in the company of Hopper's own works. Beyond this, there is no evidence that Café Terrace at Night exercised an influence on Nighthawks. Although there is no evidence at all (other than the fact that Hopper admired the story), Levin also

suggests that he may have been inspired by Ernest Hemingway's 1927 short story, The Killers.