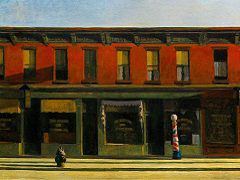

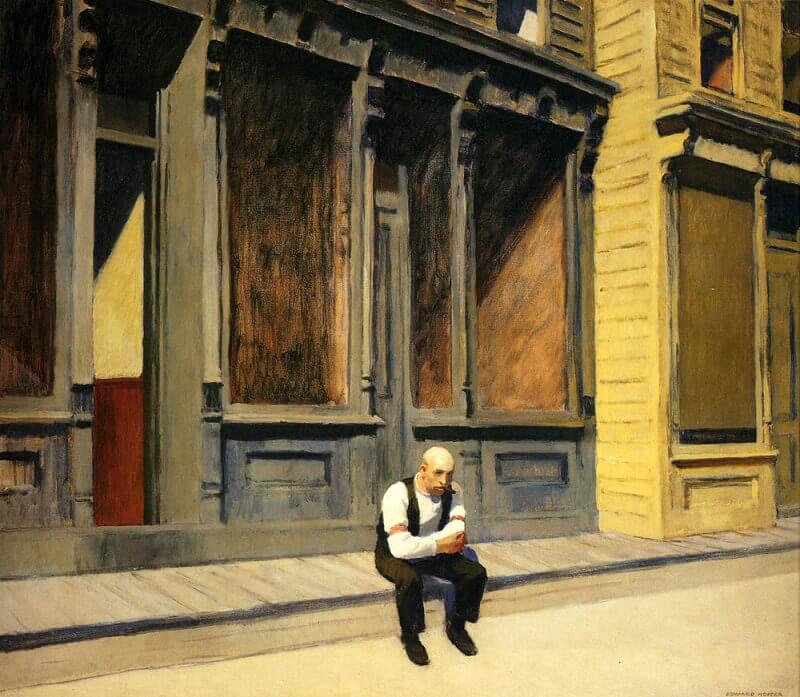

Sunday, 1926 by Edward Hopper

The people Hopper depicted all belong to the white middle class. We search his pictures in vain for other ethnic groups, not to mention signs of racial or social tension, or of the differences between rich and poor. Hopper's people are not involved in protests or strikes, demonstrations or meetings. They appear to accept their fate passively. The world they live in is strangely static, the streets largely empty of passersby, hardly a car or truck on the road. No tourist, no stranger has strayed into this silent world. All the windows are closed, and no movement is detectable behind them. It seems to be perpetually Sunday, the city abandoned (or asleep), and for the old man sitting in his shirtsleeves on the sidewalk in Sunday, 1926, this Sunday emptiness is apparently even harder to bear than the weekday vacuum, even more meaningless, more of a dead end. This is a world without a future. And perhaps the oddest thing of all - it includes no children. Hopper never portrayed a child. His is a world of adults condemned to extinction, and conscious of the fact.

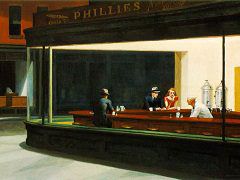

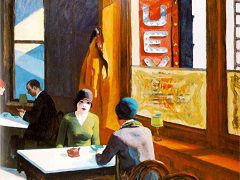

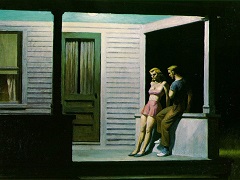

Hopper's figures are introverted people who communicate very little with one another despite the enormous psychological tension under which many of them evidently stand. They have difficulty in expressing themselves, in overcoming their inhibitions. The significance of this may be gauged by comparing Hopper's figures with those of Edvard Munch. Munch, too, depicted people who were tormented by mental conflicts, but at least they were sometimes able to unburden themselves in a scream. Hopper's people lack any such outlet.

Hopper was apparently averse to depicting extreme situations in life. There are no accidents, no sickness and death in his pictures, no reference to injury or physical disablement. Yet subliminally sickness and death do seem to be present, for we find ourselves asking how often his figures contemplate such things. And since their main occupation is waiting, we might well ask whether, apart from the hopes they still cherish, death might not be one of the things they are waiting for when they sit down in the evening sun (People in the Sun).

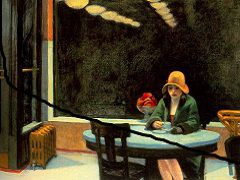

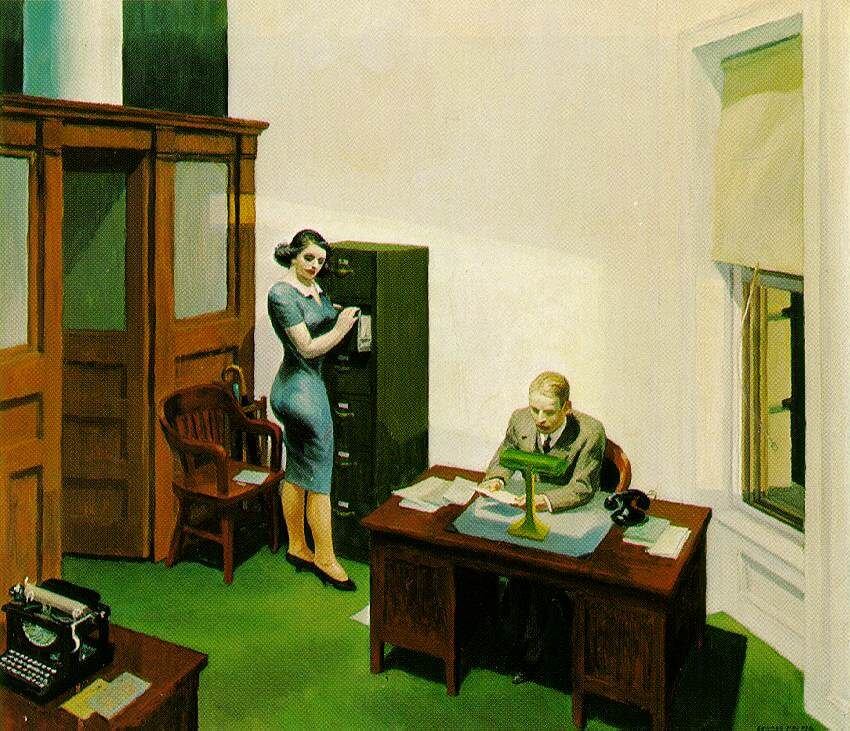

Hopper depicts people in places where their daily lives are played out: offices, restaurants, movie theaters, trains, hotels. And he makes it perfectly clear that all of them belong to the working world, bound by commitments and obligations, carrying out an occupation that has worn them to its mold. They are office employees, small businesspeople, tenants, pensioners; they work as waitresses or waiters, train conductors, gas station attendants, cleaning ladies, theater ushers, hairdressers, secretaries. They live humble lives, eat at cafeterias or automats or hot dog stands, but they do not go hungry and they still have a roof.